India stands today in an ambiguous calm. The political climate is charged: elections marred by whispered allegations of fraud, regional tensions simmering, and the pressures of an unpredictable international order weighing heavily on the nation’s stability. Yet, the bustling and chaotic streets, almost serene in their familiar disorder, can deceive the untrained eye. Beneath this surface lies a quiet, watchful tension. The institutions that have long safeguarded the state’s grip on power stand alert, none more crucial, and none more contested, than the police.

The Supreme Court of India, in words that cut past decades of official rhetoric, has declared that the police “has not come out of its colonial image despite six decades of Independence… largely considered as a tool of harassment [and] oppression and surely not considered a friend of public.” This is not merely perception. Hard data confirms the crisis of trust—The Status of Policing in India Report (SPIR) found that less than 25% of citizens in 22 states express high confidence in their police. In a democracy that claims to be the world’s largest, such a deficit is not merely troubling, it is an existential fault line.

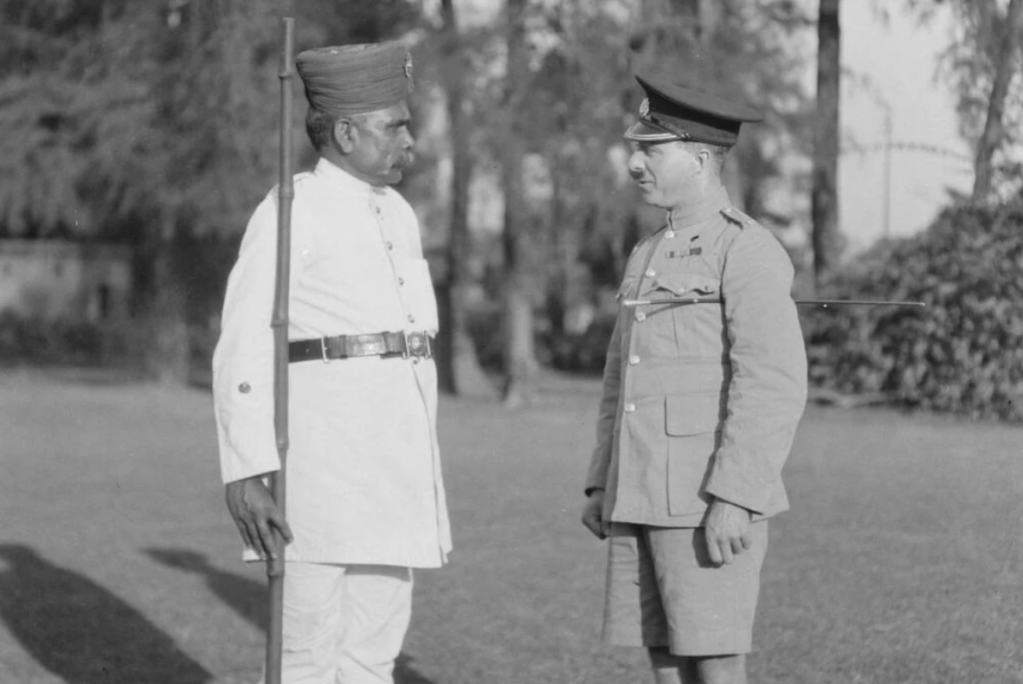

This broken compact between citizen and constable is not accidental. In fact, it is working exactly as designed. The architecture of Indian policing was conceived by colonial minds in the wake of the 1857 rebellion. Not as a protective institution of public service, but as an arm of imperial discipline. The 1860 Police Commission and the resulting Indian Police Act of 1861 were created not to police by consent but to police by command. Yet, nearly a century after independence, they remain in place, almost unchanged.

A Design for Domination

In London, Sir Robert Peel’s police model flourished on the maxim that “the police are the public and the public are the police.” Legitimacy, in this philosophy, depended upon trust and shared purpose. But in colonial India, this principle was inverted. The Raj could not afford, nor did it desire, a police that drew legitimacy from the consent of the governed. Instead, it created a force designed to monitor, to pre-empt dissent, and, when necessary, to crush it with decisive violence.

When the 1861 Police Act came into being, it enshrined into law the operational principles laid down by the 1860 Commission. These included subordination of the police to the executive, vast discretionary arrest powers on mere suspicion, and immunity from prosecution for “good faith” acts; even if those acts trespassed legal or moral boundaries. Public spaces would be policed with tight control; gatherings could be dispersed at will. Vague, catch all, provisions against “nuisance” and “annoyance” criminalized everyday life, especially for the poor.

This was no accident of drafting. These laws were perfect tools for pre-emptively breaking up gatherings of nationalists, labour organisers, or students. A political discussion could be framed as “misbehaviour,” a protest chant as “annoying passengers,” and a gathering to plan resistance as intending to “provoke a breach of the peace.” Suppressing dissent and granting wide discretionary powers were features, not flaws. The context was clear: a mutiny that had nearly toppled British rule demanded a police force to ensure it could never happen again.

A Colonial Skeleton in the Republic’s Closet

The disquieting truth is that, more than 75 years after Independence, this colonial skeleton remains intact. Many Indian states have either kept the 1861 Act on their books or passed new legislation that reproduces its essence almost verbatim. In Uttar Pradesh, Tamil Nadu, Gujarat, Delhi, and elsewhere, the statutes still grant sweeping powers to ban processions, arrest on suspicion, and criminalise undefined “annoyances.”

Some states like Maharashtra, Gujarat, Kerala, and Delhi have enacted their own Police Acts, but even these are closely modeled on the Act of 1861. The Gujarat and Maharashtra Acts, both descendants of the Bombay Police Act of 1951, continue to emphasize control rather than service. They grant extensive powers to regulate assemblies and processions, and to take preventive action against individuals. The framework is hierarchical, with superintendence vested entirely in the State Government.

The result is a continuity of colonial logic in everyday policing. Consider the minor offences scattered across these statutes:

- “Disregarding the rule of the road” (Gujarat s.99, Delhi s.80, Maharashtra s.99).

- “Causing obstruction or mischief by animal” (Delhi s.81, Gujarat s.100, Maharashtra s.100).

- “Behaving indecently in public” (Gujarat s.112, Delhi s.93, Maharashtra s.112).

- “Being found under suspicious circumstances between sunset and sunrise” (Gujarat s.122, Delhi s.102, Maharashtra s.122).

These are relics of 19th and mid-20th-century understandings of order. For the British, stray cattle, noisy streets, and unregulated gatherings symbolised “native disorder” that had to be tamed. Criminalising these trivialities was about projecting imperial efficiency, not about genuine safety. Today, the same provisions continue to arm the constable with wide discretion, enabling harassment rather than service.

A System That Works as Designed

SPIR data shows how this history bleeds into the present. Nearly half the police rank-and-file believe preventive arrests of “anti-social elements” are “very useful,” a belief that rises to three-quarters in Gujarat. More than half support “tough methods” to instil fear. Astonishingly, 27% justify mob violence in cases of sexual harassment—an extrajudicial mindset born of a policing model built on fear, not legitimacy.

In 2022 alone, police executed 1.2 million preventive arrests under Section 151 of the CrPC—a continuation of colonial logic that presumes guilt before crime. In Gujarat, according to the 177th Law Commission Report, preventive arrests (189,722) far exceeded arrests for substantive offences (113,489). Minor infractions such as loitering or nuisance still dominate arrest figures, just as they did under the Raj.

And accountability remains elusive. Between 2005 and 2018, despite 500 documented custodial deaths, not a single police officer was convicted. High-profile incidents, from alleged “chest-height” firing on protesters in Assam to brutal custodial beatings in Tamil Nadu, are not anomalies but symptoms of a system that grants vast power and minimal scrutiny.

The Reform That Was Never Realised

India has never lacked blueprints of reform. The 2006 Prakash Singh v. Union of India judgment offered seven directives for insulating the police from political manipulation, ensuring fixed tenures, separating investigation from law-and-order duties, and establishing independent complaints authorities. That same year, the Model Police Act proposed a paradigm shift. Its preamble explicitly called for a service-oriented police, “free from extraneous influences and accountable to law,” with human rights at its core.

The Act extended its scope beyond day-to-day governance to robust accountability mechanisms, community policing, strategic planning, and welfare of police personnel. It was a direct response to the reality that Indian policing had remained tied to control while the world had moved on.

Yet, progress has been glacial. Most states have either ignored the Prakash Singh directives or selectively complied while retaining executive dominance. Even when adopting new laws, states have smuggled in colonial DNA. For instance, in Maharashtra, Section 22(N)(2) allows the Chief Minister to override fixed tenure protections for top officers, reducing reform aimed at decreasing state influence over police authorities to mere “dikhavat”.

How the World Moved On—Without Us

The irony is sharp. Britain, which exported this model to India, has long since abandoned it at home. It’s Independent Office for Police Conduct enjoys statutory powers and public accountability. South Africa created an Independent Police Investigative Directorate after apartheid. Canada’s British Columbia has a Police Complaint Commissioner independent of government.

India, the largest democracy in the Commonwealth, continues to operate under the architecture of an empire it overthrew generations ago.

Breaking the 1861 Pact

India has begun to decolonize all its criminal codes. The Home Minister declared that “justice replaces punishment” in the new laws, and the centre has stressed that British-era laws focused on colonial control have been replaced by frameworks in sync with contemporary Indian jurisprudence. But these alleged legislative triumphs ring hollow so long as the institution that enforces them remains trapped in 1861.

The inescapable conclusion is that India’s police is not broken. It is functioning exactly as designed: to guard power, discipline subjects, and maintain order without necessarily guaranteeing justice. That is the DNA of a colonial force. A democratic republic must demand a new genetic code.

This requires more than tinkering: repealing the Police Act of 1861 and its derivatives; enforcing Prakash Singh in both letter and spirit; decriminalising vague nuisance and loitering offences; and establishing truly independent oversight with teeth.

Calm is not consent. Silence is not peace. Order without justice is merely the stillness of fear. If India is to complete the journey from subject to citizen, from ruled to self-governed, then the police, our most visible and accessible arm of the state, must make the same journey. That means not reforming the 1861 police, but finally resigning it to history.

Leave a comment